Robert R. Douglas:

Robert R. Douglas:

A Journalist Who Got It Right

By SCOTT MORRIS

White County Historical Society 2000 White County Heritage

Robert R. Douglas

was 20 years old when he received maybe the most important news

of his life: Japan had surrendered. World War II was over.

Douglas, a sailor on the carrier Essex in

the Pacific, was asleep when the word came. “Somebody woke

me up and told me the news,” he recalls. “I went back

to sleep.”

His low-key response belied the relief he

felt. Since joining the Essex in September 1943, Douglas had seen

heavy combat on what was known as “the fightingest ship in

the fleet.” The Essex served in more than 80 operations and

won 13 battle stars, more than any other ship in the Pacific.

In the first serious combat Douglas saw, the six ships of the

task group led by the Essex came under attack from about 130 Japanese

planes. Later, during the battle of Okinawa, the Essex and its

support group were attacked 350 times in three months.

Douglas had known that if the Japanese didn’t

surrender, his ship would be in the thick of an invasion that

was expected to cost 1 million American lives. “I thought

my number was up,” he says. “I had never thought so

before, but I had a sense that the odds were getting real thin.

We’d been so lucky.”

As it turned out, his ship, so long at sea,

was sent home immediately after the surrender was announced. The

Kensett, Arkansas, native who had never seen the ocean before

entering the Navy, was on his way to a long and distinguished

career in journalism, a profession he had picked for himself while

still in the sixth grade.

Standing on the carrier’s flight deck

during that final cruise, Douglas felt a sense of euphoria. “That

was a great time of life,” he says. “Everything was

going to be OK. The future couldn’t have been brighter.”

An avid reader of the Arkansas Gazette –

“It was the usual male progression from the comics to the

sports page to the general news columns” – Douglas had

taken an early interest in public events. He recalls driving with

his parents to the White County courthouse in Searcy to watch

election returns in the 1930s. And, as a young boy, he formed

a friendship with an adult neighbor who would go on to fame and

infamy in state and national politics – Wilbur D. Mills.

After leaving the Navy, Douglas enrolled

at the University of Arkansas, where he served as managing editor

of the Arkansas Traveler before graduating with a degree in journalism

in 1948. While visiting a friend at the Gazette, he was hired

as a general assignment reporter, a job that paid him $40 a week

and began his 33-year association with the oldest newspaper west

of the Mississippi.

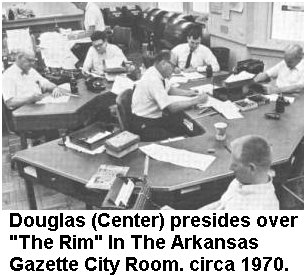

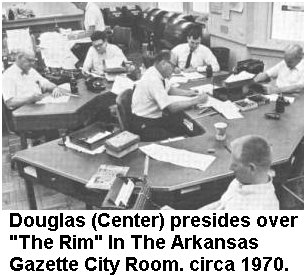

During his time at the Gazette, Douglas

also worked as a copy editor, telegraph editor, news editor, and

night managing editor. He was named managing editor Feb. 14, 1972.

Douglas held editorial positions when the paper won two Pulitizer

Prizes, the Freedom House Award, the John Peter Zenger Award,

the Elijah Lovejoy Award – all earned as a result of its

coverage of the 1957 crisis at Central High School. He led one

unsuccessful newsroom strike (in 1949-50) and served as managing

editor when a second attempt to organize newsroom employees failed

(in 1974). Also as managing editor, Douglas formed the Gazette’s

first team of investigative reporters and expanded the paper’s

staff. He presided over the newsroom when Martha Mitchell made

her famous late-night phone calls from Washington and when the

Washington Post called to ask for help investigating an out-of-control

Arkansas politician.

That politician was Congressman Wilbur Mills,

the former White County judge who had taken a young Douglas to

ball games and movies. “It was hard for me,” Douglas

says. “I went the other way and overdid” the paper’s

coverage of Mills’ drunken escapades with a stripper. To

his credit, Mills never asked Douglas to kill the story, but when

it was over he did invite the newspaper editor to his office.

“For an hour and forty minutes I listened to him talk,”

Douglas says. “He said he didn’t remember any of it.

He’d been suffering from a serious back problem, and he said

the doctors who prescribed tranquilizers for his pain hadn’t

told him not to mix them with alcohol. I believed him.”

Douglas left the Gazette in 1981 to become

chairman of the UA journalism department. “The department

was underfunded,” he remembers. “They were doing the

best they could with no equipment. They were teaching one class

in the hall.”

Douglas worked to secure the department’s

full accreditation and to start a master’s degree program

that combined journalism with other disciplines such as history

and political science. One of his more memorable battles rose

out of his efforts to name the department for its founder, Walter

J. Lemke. After the dean’s office had rejected the idea three

times on the grounds that no other UA department was named for

an individual, Douglas asked alumni to write letters to the chancellor

urging the change.

“The chancellor called one day and

said, ‘There’s a move on to name the department for

Walter Lemke. Would you object?’ I said, ‘No, I guess

that’s OK.’”

Douglas, who admits he wasn’t entirely

sure what to do the first time he stepped into a classroom, now

says, “Teaching has been very rewarding. I enjoyed the students

and how receptive they were to learning and what great people

they were. They were interested in the same things I was as a

student: news-papers, newspaper presentation of the news and newspaper

ethics."

Douglas retired from the University in 1991. He is married to

Martha Leslie, the Gazette’s former radio and TV editor.

He writes a weekly column for the Democrat-Gazette and does some

newspaper and legal consulting.

Douglas’ idea of what constitutes good

journalism hasn’t changed over the years: “A newspaper’s

mission is to inform, entertain, and get it right. I don’t

like gimmicks. I like straight journalism. That’s what really

sells newspapers, and that’s what we ought to do.”

The preceding was written for the program for Bob Douglas

Day, October 29, 1999, in the Department of Journalism at the

University of Arkansas. White County Historical Society president

Eddie Best and his wife Pat were members of the Gazette staff

with Douglas from 1954 until 1965. Pat Best returned to the Gazette

in 1972 and served as Douglas’ administrative assistant until

he left for the U of A in 1981.

The preceding was written for the program for Bob Douglas

Day, October 29, 1999, in the Department of Journalism at the

University of Arkansas. White County Historical Society president

Eddie Best and his wife Pat were members of the Gazette staff

with Douglas from 1954 until 1965. Pat Best returned to the Gazette

in 1972 and served as Douglas’ administrative assistant until

he left for the U of A in 1981.

The preceding was written for the program for Bob Douglas

Day, October 29, 1999, in the Department of Journalism at the

University of Arkansas. White County Historical Society president

Eddie Best and his wife Pat were members of the Gazette staff

with Douglas from 1954 until 1965. Pat Best returned to the Gazette

in 1972 and served as Douglas’ administrative assistant until

he left for the U of A in 1981.

The preceding was written for the program for Bob Douglas

Day, October 29, 1999, in the Department of Journalism at the

University of Arkansas. White County Historical Society president

Eddie Best and his wife Pat were members of the Gazette staff

with Douglas from 1954 until 1965. Pat Best returned to the Gazette

in 1972 and served as Douglas’ administrative assistant until

he left for the U of A in 1981.