The Long Road to Romance

The Civil War Odyssey of Asbury Hooks, 19thArkansas Infantry

by Jerry Hill

Houston, Texas

My great-grandfather, William Asbury Hooks, is buried in the Romance cemetery, because he lived a majority of his life there in White County. However, he certainly took a long journey to eventually arrive at that place.

William, or as he was often known, Asbury, or W.A., was born on January 7, 1844 in Georgia. Census records typically list his first name as Asbury so we’ll consider that to be the name he normally was called by, although his military records use his initials of W.A. His father John brought the family to Columbia County, Arkansas about 1850 where Asbury would grow up with his six brothers and four sisters. After the outbreak of the Civil War he entered the Confederate Army. Asbury was unable to write and only made his mark but through the narratives and records left by others who traveled with him we are able to relive his experiences as a confederate soldier.

After Fort Sumter was attacked on April 12, 1861, Arkansas signed the ordinance of secession from the Union on May 6, 1861. Asbury Hooks enlisted nine months later with a group of volunteers from Columbia County. His enlistment was on February 26, 1862 for a period 12 months. That was shortly after his 18th birthday. Little did he know those 12 months would stretch into several years.

Asbury was assigned to the 19th Arkansas Infantry regiment, which had been organized at DeVall's Bluff, Arkansas, in 1861 under Colonel H.P. Smead of Columbia County. The regiment included companies from Columbia, Lafayette, Union, Ouachita, Hot Springs, and Union Counties. The regiment later reorganized by electing Tom Dockery as its Colonel. In recognition of the name of its commander, Dockery’s name is often appended to the name of the unit. The regiment would have numbered about 600 soldiers. There were 10 companies in the regiment and Asbury Hooks was assigned to company B with other men from Columbia County. This county must have had strong sentiment for the war because four of the 10 companies were made up of recruits from Columbia County.

Unlike some Arkansas military units that went east and participated in the eastern campaign at places such as Gettysburg, the 19th Infantry Regiment went into action as part of the Confederate Army of Trans-Mississippi. The unit moved to Memphis, then Fort Pillow, Tennessee. In October 1862 the regiment was in Mississippi and participated in the battles of Corinth and Hatchie Bridge, reporting 129 casualties in these particularly bloody engagements.

The company commanders of the 19th Arkansas Regiment made notes on their regular muster roles of the activities of their regiments. Here are some remarks appended to the October 31, 1862, muster roll noting the recent travels of Company B:

Left Saltillo September the 12th. Arrived at Iuka Sep. 14th. Federals attacked us on the 18th. A fight ensued. We evacuated the place on the 19th. Arrived at Baldwin on the 22nd. Left Baldwin on the 24th for Corinth. Arrived at Corinth on the 3rd Oct. A fight ensued on the 3rd. The Enemy was driven back. The engagement was renewed on the 4th. A general charge was made on the fortifications about 10 o’clock. We was repulsed & retreated to Holly Springs.

At the battle of Corinth Mississippi, the 19th was attached to General Cabell's Brigade, consisting of the 18th, 19th, 20th and 21st Arkansas Regiments, the 8th and 12th Arkansas Battalions, and an artillery battery. The units had been decimated by disease prior to the Corinth fight, and so were under-strength when the assault was made. Even with the relatively small number of men present, the brigade suffered something like 650 casualties. Cabell reported:

The courage and daring of my men, who shot the enemy down in their trenches, is beyond all praise. The ground in front of the breastworks was literally covered with the dead and wounded of both friend and foe, the killed and wounded of the enemy being nearly if not fully two to our one. Those left presented the appearance of men nearly whipped, and convinced me that it was nothing but their reinforcements and superior numbers that kept them from a total rout.

A letter written on October 11th by James P. Erwin, the adjutant in Dockery’s Regiment, says:"

Our brigade (Cabell's) now numbers only 511 effective men, and lost 889 men in three day's fighting...The loss of our regiment is greater than that of any other regiment in the brigade. We went into the fight with 179 men and lost in killed, wounded and missing 129."

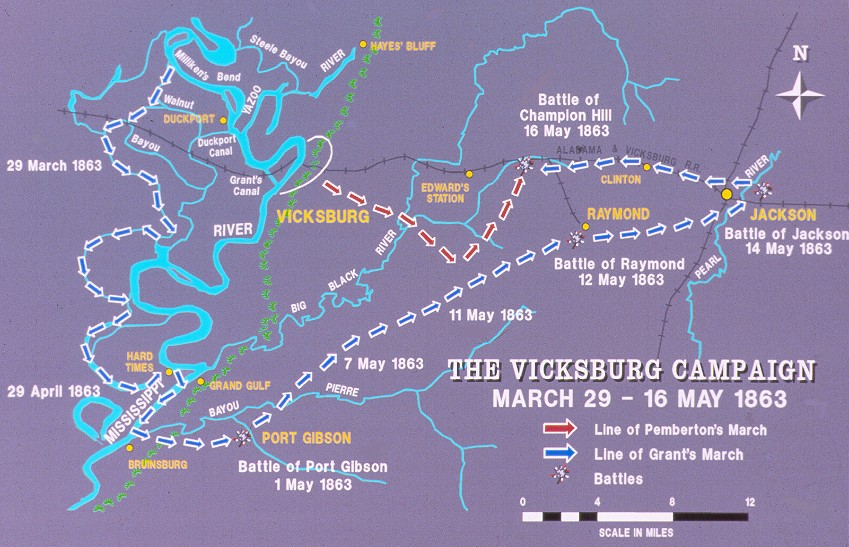

Following the battle at Corinth, Mississippi, the 19th Arkansas Infantry was engaged in a number of various skirmishes, engagements, and battles on both sides of the Mississippi River. The men arrived in the vicinity of Vicksburg in January of 1863 and took up the defense of the city. The unit was engaged in one of the major battles there at Port Gibson on May 1st. After the Union forces established a siege line around Vicksburg and were unable to capture it, they began to move toward other key confederate targets. In May, Union troops led by General U.S. Grant circled to the south of Vicksburg, then turned east to capture Jackson, Mississippi. By mid-month they turned back toward Vicksburg and a force of Confederates under General Pemberton moved out to meet them. The force included the 19th Arkansas Infantry with Asbury Hooks among them.

The two opposing forces met about halfway between Jackson and Vicksburg at Champion Hill on May 16th.

Map Showing the Location of the Battle of Champion’s Hill

In the January 1910 issue of the Confederate Veteran, another member of the 19th Arkansas Infantry, Private A.H. Reynolds, recounts the engagement in an article titled Vivid Experiences at Champion Hill, Miss. Here are the highlights of his article:

Just at sunrise on May 16, 1863, the left wing of Grant's army opened the engagement at Champion Hill with artillery which lasted some time before a general engagement followed with musketry front all along the line. I belonged to Company F, of the 19th Arkansas Regiment, commanded by Col. Tom P. Dockery, then attached to Green's Brigade and Bowen's Division.

When the Federal battery opened we were lying just over the brow of the hill on our extreme right, where we had lain since about two o'clock that morning. The firing commenced from the batteries which were in our immediate front, and we moved out on top of the hill and a little to our left in plain view of the batteries, but did not answer them. They were not firing at us, but at some troops that were marching to the attack near the Champion Negro quarters and about the center of our line. Some general and his staff were near by watching the maneuvering of Grant's army. The hill was high with a plain view and about half a mile or more southeast of the Negro quarters on the road leading toward Grand Gulf.

I could not see that their batteries were doing any great damage. However, it was one of Colonel Dockery's hobbies to volunteer to take some battery or storm some difficult stronghold with his legion, as he often called the old 19th Regiment, which was a good-sized one then.

The Colonel had just volunteered to take his regiment and capture that battery. He was refused, but shortly got a job without volunteering. There was some heavy fighting going on near the center at this time, and occasionally a courier would come dashing up. By this time several officers had congregated near us, with Colonel Dockery in their midst. He had just ridden back to where we were when some fellow came down the road as if racing for life. He rode up to the little bunch and halted. Colonel Dockery was given orders to take his regiment and reinforce the center.

As the adjutant rode off Colonel Dockery, as cool as an ice-berg, gave the command: "Attention, load at will; load." My heart got right in my mouth, and I believe every other fellow was in like condition; but not a word was spoken by any one. The next order was: "Forward, double-quick, march." As we passed the squad of officers one of them said: "Turn in at those quarters." When we got there, Colonel Dockery had preceded us and was sitting on his horse as cool as ever and gave a ringing command, "Halt on the right; by file into line; double-quick, march;" and quickly we were in line and facing a regiment of thoroughly routed soldiers. I should like to know who they were. The next command was: "Fix bayonets and hold fire until ordered." With a forward march we passed those troops that were falling back, and then we were ordered to charge. We had caught the enemy with empty guns, and they gave way easily.

We were charging up the long slope from the Negro quarters to the highest peak of Champion Hill and almost parallel with the public road to Bolton. At the top of the hill we met another long line of blues climbing the steep hill. They were within eighty feet of us when we gained the top of the hill, and without orders it seemed as if every man in our ranks fired at once. Never before nor since have I ever witnessed such a sight. The whole line seemed to fall and tumble head-long to the bottom of the hill. In a moment they came again, and we were ready and again repulsed them. And again and again for several hours in this way we held them at bay, when we charged them and gained the top of the next hill, the spindle top to which place Gen. S. D. Lee always contended the Arkansas troops advanced.

When we reached there we were ordered to fall back, as we were being flanked by Logan's Division. About twenty of us, mostly from my company, were left to cover the retreat, being sharpshooters. We stopped in a hollow that headed up near the Bolton road. After waiting until the command was clearly out of sight, six of our number and I, went out where we could see over the hilltop. A regiment of Federal infantry was just filing out of the big road to our right and about eighty yards away and advancing at trail arms in an oblique direction toward us, their commanding officer riding just in front and to our right. When they had covered about half of the distance between us, Billy Watts knelt beside a little oak tree and fired. When the officer fell (as if dead or mortally wounded) each of us singled out a man and fired.

Immediately I primed my gun, a Springfield rifle, and was loading it and watching for another shot and walking backward down the hill, dragging my gun butt on the ground, intending to get my man when they came over the hill, and had just rammed the ball home when my foot came in contact with a root of a huckleberry bush that had been rooted up and I fell sprawling with my head down hill and before I could recover they were upon us. They fired a volley just as I fell, and I have always felt that the fall saved my life. The next instant they were at us with bayonets. I raised on my right elbow just as a big fellow was in the act of thrusting his bayonet through me and fired. The muzzle of my gun was within four feet of his breast and loaded with a Springfield rifle ball and a steel ramrod.

I had fallen within ten feet of the hollow where we had previously been. With what strength I had left I sprang over the precipice of the cave; but before I could scramble down the lifeless corpse of my antagonist preceded me with a heavy thud in the slush below. In the next minute we were prisoners of war.

Asbury Hooks was among the soldiers of the 19th who were captured by the Union forces at Champion Hill. Federal authorities assembled about 4400 confederate prisoners who had been captured at Champion Hill on May 16th and also at the Battle of Big Black Bridge the following day, May 17th. They put them aboard four river steamers at Young’s Point, Louisiana, upriver from Vicksburg at the mouth of the Yazoo River, and sent them to Memphis on May 25th. With this number of people aboard just four vessels, it must have been severely cramped for Asbury and his fellow soldiers onboard. The prisoners were not allowed to disembark and were transported to Cairo, Illinois where they arrived on May 31st. Officers and men among the prisoners attempted to organize a seizure of at least one transport en route from Memphis to Cairo but the plot was discovered before they could bring it off.

The men were offloaded onto trains of the Illinois Central Railroad and transferred to Camp Morton in Indianapolis, Indiana. Housing of confederate prisoners became a problem for the North because their penitentiaries and other facilities had become overloaded. Because of this, more often than not, prisoners were paroled and exchanged on the battlefield. Camp Morton had been a training location for Union troops and with the overflow of POWs it was now being put to use as a prison camp with guards being drawn from less able men who formed the Indiana home guard.

When Asbury Hook’s group arrived the officers were separated and sent to Johnson’s Island on Lake Erie while the remaining enlisted prisoners were broken into two groups. The first group consisted of several hundred who were left behind at Camp Morton due to illness and or political reasons. Among these new prisoners were 250 East Tennesseans who took the oath of allegiance and enlisted with the Union army. The remainder, which amounted to about 3750, were delivered to Fort Delaware on the east coast. They traveled by train from Indianapolis to Columbus, Ohio, Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, and Philadelphia. From Philadelphia they were taken south by boat to Fort Delaware about June 16th.

Many of the men were sick when captured and they were not adequately cared for in terms of food or medical attention en route to Fort Delaware. Prisoners began dying almost immediately upon arrival and a high death rate prevailed for several months.

Fort Delaware is situated on an Island in Delaware Bay, about 40 miles south of Philadelphia. It was completed in 1859 for the purpose of protecting the city of Philadelphia from invasion via the Delaware River but that threat never happened. It sits on an island surrounded by water, which made it ideal to convert to a prison camp. By May of 1862 barracks had been added to house Confederate POWs and by June 1863 when Asbury Hooks arrived there were 8,000 prisoners on the island. Between 1862 and 1865 about 2700 prisoners died at the fort because of unhealthy conditions and medical neglect.

One of the soldiers captured with Asbury Hooks was Elihu C. Beckham, a Sergeant in Company “K”, 21st Arkansas. He recounted his memories of being a POW at Fort Delaware in an issue of the Melbourne Times, dated September 6, 1906. Here is how he described it:

There is probably ten acres on the island, which, at high tide, would be covered in water to a depth of about six feet. The tide water is about eight feet and there is a levee around the beach of the island which keeps the water out.

The fort is situated on the north side of the island, not more than thirty or forty feet from the Bay, three miles from the New Jersey and two miles from the Delaware shore. The fort is built of granite; that is, the outside wall is granite, lined inside with two feet of brick, making the wall seven feet thick. The wall is about 300 feet square and forty feet high. The ground is raised inside so as to be above high tide. There is a moat around the wall some thirty feet wide and eight or ten feet deep, with a bridge across it leading into the fort, which is the only means of ingress. The door has a large iron shutter and it is six or seven feet from the water in the ditch up to the door and the bridge can be drawn inside and the door closed, so that if an enemy were to land infantry on the island they could not get to the wall; and besides, there is a flood gate that could be opened by those in the fort which would let the water through the levee, and at high tide would cover the island six feet in water in a few minutes and drown them out.

Fort Delaware as it Appears Today

(Courtesy of the Fort Delaware Society)

Our quarters were west of the fort some sixty yards, which were barracks of box houses, capable of holding two or three hundred men each. There were about ten thousand prisoners there. We had free access to the bay on the south side of the island. The water was just a little brackish, so we had to have all the water shipped to us. There were plenty of fish there and we caught thousands of them, mostly cat, from six to fifteen inches long.

The prisoners amused themselves in various ways some reading, some singing, some preaching, some fiddling, and dancing, some making jewelry of gutta-percha, bone, shell and so on and not a few gambling. Between the barracks and bay on the south side was a square piece of land, smooth and level as a floor, that we called “Hell’s Half Acre”, where those who wished to spend their time gambling would meet. The various games were carried on such as euchre, poker, seven up, three up, odd trick, whist, casino, faro, keno, monte, Honest John, and in fact, every game known, and a number that were unknown to me. I took no hand in the gambling but spent my time in making rings, fishing and fooling about making things.

Thousands of Confederate POWs captured at Gettysburg began to pour into Fort Delaware in early July. By mid August there were about 12,500 prisoners in a facility designed to hold only 10,000. Releasing the prisoners through an exchange was the only practical way to ease the crowding.

A formal arrangement for exchange of prisoners had been established between the North and the South under an agreement that was called the Dix-Hill Cartel, which had been negotiated between John A. Dix, a Union general and D. H. Hill, a Confederate general in 1862. Under the cartel there was a formula for exchanging the numbers of prisoners. It was not a one-for-one exchange but was based on rank. Some of the equivalencies that were established were:

- A general commanding in chief or an admiral for sixty privates or common seamen.

- A lieutenant-colonel or a commander in the Navy for officers of equal rank, or for ten privates or common seamen.

- A lieutenant or a master in the Navy or a captain in the Army or marines for officers of equal rank, or six privates or common seamen.

- Second captains, lieutenants or mates of merchant vessels and all petty officers in the Navy and all non-commissioned officers in the Army or marines exchanged for persons of equal rank, or for two privates or common seamen

- Private soldiers or common seamen exchanged for each other, man for man.

City Point, Virginia was a small town on the James River near Richmond which was primarily a shipping port and used as an exchange point for Prisoners of War between the Union and Confederates. City Point is the modern day town of Hopewell, Virginia, and had the advantage of being able to handle large deep draft vessels.

Prisoners would have been brought to City Point, from a Union prison by boat, under a flag of truce. The boat would return north with a load of Union prisoners that had been held by the Confederates.

Attempts by the commander of Fort Delaware to alleviate the overcrowding by sending sick or disabled prisoners to City Point, Virginia, for exchange in July were thwarted by Federal authorities. Asbury Hook’s name appears on a July 1863 roster of Fort Delaware POWs actually sent by steamboat to City Point for delivery only to be turned around and off loaded back at Fort Delaware.

Another Union POW camp called Point Lookout was opened in September 1863 at the southern tip of Maryland. Asbury Hooks was one of the POWs sent from Fort Delaware to Point Lookout on September 20, 1863. He was paroled for exchange at Point Lookout on December 24th and delivered to City Point, Virginia on December 28, 1863 with some 505 confederate prisoners. From City Point, the returning confederates were moved by steamboat up the James River to the docks at Richmond and the able bodied marched to Camp Lee on the West side of Richmond. On January 1, 1864, Asbury made his mark on a clothing receipt and that is his last military service record.

Another Confederate soldier, Elihu C. Beckham, who was held as a POW with Asbury describes their release in his memoirs as follows:

On the 24th day of December, after being paroled, 525 of us were sent to City Point for exchange but the exchange was not affected and we were exchanged only on parole. Next morning, Christmas, we anchored at Fortress Monroe, where I saw a Russian man-of-war, which was a powerful boat that carried seventy-two guns. On the 26th we anchored at City Point, lay there till the 28th, when we were met by a boat with a like number of prisoners and we marched off on to our boat and they to theirs, the officers counting us like a drove of sheep. About dark, the 28th, we landed at Richmond, Va.

On New Year’s Day, 1864, the ladies of Richmond gave us a fine dinner but the weather was so cold that we did not enjoy it as we should have liked.

On the 2nd we drew six month’s pay and on the 7th we were furloughed...and they gave us transportation to any point they had in possession east of the Mississippi.

Returning to Arkansas from Virginia was problematic because the railroads had been destroyed in many areas and Federal troops were in control of the Mississippi corridor. The men were given Confederate government railroad passes to get as far west as Jackson, Mississippi. From there they had to travel cross-country. Beckham describes their travel beyond Jackson in the following way:

“The next thing was how to get across the Mississippi River. Some said to cross at one place and some said another but I finally found an old citizen who told me that the surest plan was to cross at Rodman, about one hundred miles below Vicksburg. So I started, in company with F.O. Pittman and Tom Murry, thinking the other boys would go above.

We struck the swamps where the bottoms were narrow and were soon on the bank of the river in a heavy canebrake. We saw a smoke and advanced with caution but soon found that it was some of our boys camped there. So there we were, thirty-one of us, with nothing to eat and had not eaten anything since early that morning, and the Federals were thick on every road but, fortunately, there was no road where we were. We lay there that night and next morning held a council, and it was agreed that some two or three men go back and find a house and try to get a boat. Bill Caldwell and two others went and were gone all day, and we concluded they had been captured, but about 8 o’clock that night they returned and had an old man with them who said his name was January, and had a skiff on a wagon and two Negro men with him. We paid him $50 each to put us on this side of the river, on the night of the 23rd, at the very point where John A. Murrell swam it on his black horse.

When we crossed there was a gunboat in sight above and below. As soon as

we were across we lit out, seven of us together, and walked hard for two or

three hours, as we thought, square off from the river in a swamp.

Finally we concluded to lay down and rest till day thinking that we were a good distance from the river.

Directly we were awakened by the escaping of a boat and, there it was, less

than one hundred yards of us and directly in our course. We then saw

that we had walked a circuitous route and were back to near where we crossed

the river. We started again and, that time, kept on a straight course

and about sunrise we came to a house and ordered breakfast for seven hungry

men. It had been forty-eight hours since we had tasted food. In

about two hours breakfast was ready and we went in, and I don’t think I ever

saw provisions disappear as fast in all my days, according to the hands.

Just after we started and, before we had gotten out of sight, we saw a man

coming at full speed and motioning with his hat for us to run. We

stopped till he came up. He said to run quick, that the Feds would be

there in a few minutes, but that if we could make it to the back of the field,

a half mile distant, we would be safe for a time. So away we went,

helter skelter, just as hard as we could but we had eaten so much we could not

run fast. I never was so tired in all my life. It was a tight fit

for us to strike a trot but if we could reach the fence we could rest.

Finally, when we did get there, there was hardly a man among us who could

speak and we just fell over the fence and lay as we fell at least an hour.

We could see the road and the house and not a Yankee came along that road.

We resumed our march and traveled all day through the woods parallel with the road. About night we ventured to a house where an old Negro lived. We asked him about the Federals. He said he never saw but few and that there never had been any there. We asked him if he had any potatoes. “No, massa,’taters all gone.” We told him we would give him two dollars for a bushel. “Well, doan’ no, mabe dar’s ‘er few.” He called a boy, sent him in a cellar with a basket that would have held three bushels, told him to fill it. I went to help him and we got her full, paid him, then Murry asked him if he had any bacon. He said no. Murray told him that he would give him a dollar for a pound. “Les go an’ see den’ maby dar’s ‘er little up in de loff.” Murray followed and soon returned with five or six pounds.

We walked on four or five miles, left the road about a half mile, built a fire in a hollow close by a little branch, broiled our bacon and roasted potatoes, ate a hearty supper, spread out our blankets and slept sound till daylight. We had got separated till there were only three of us there, Pittman, Murray and myself. We walked on in the direction of Monroe, La., which place we passed about the 26th. We directed our course north, ate when we would get anything and when we could not, did without. The waters were up and we were traveling through a low level country. Sometimes we walked for miles from knee deep to our shoulders in water. Finally we came to the Salem River which was overflowing its banks, and tried to wade through a little caney swamp to the bank, but soon found out that we were too short to ford it and had to turn back, as the water was so cold that we would freeze if we did not get out. We had quit the road and were traveling by guess through the woods.

We had found that there was a picket post on the river not far below where we were and that was our only chance to get across. So we put a bold face and marched straight for the picket. You see, the Rebels held the country south of the Arkansas River at that time. The Federals held the rivers and the country on each side for a short distance but the Rebels were in possession of the country south of the railroad running from Little Rock to DuVall’s Bluff. So this was a Rebel picket and, as we were paroled, we felt sure that they would put us across. When we got there and told the ferryman that we wanted to cross the river, he said all right, but the sergeant of the guard asked us where we were going. We told him we were going home. “

Unfortunately, Beckham never made it back home. He was picked up while passing through a part of Arkansas held by Federal troops. They did not honor his status as a paroled and exchanged prisoner and sent him to the Rock Island Prison at Rock Island Illinois. He finally reached home in Arkansas in June 1865.

Asbury Hook’s release from captivity was an unusual stroke of timing. The Dix-Hill Cartel was in a state of collapse at the end of 1863. The federal perception was that all of the returned confederates were soon back in the ranks fighting. By the fall of 1863 the Federals held some 40,000 confederate soldiers in northern POW camps while the Confederates held only about 13,000 soldiers. The Federals did not need their 13,000 union troops but the Confederates were desperate to get their 40,000 men back in the ranks.

The group of 505 men who were paroled with Asbury Hooks and exchanged at the end of 1863 was among the last group released from Fort Delaware because the Federal authorities started to severely restrict the exchange of prisoners after that. Most of the rest at the fort remained until the end of the war in 1865.

It is ironic that the Union force that finally took Vicksburg met with the same recurring problem of what to do with the thousands of Confederate soldiers who had surrendered. Rather than trying to put them in confinement, they were paroled in the field. The 19th Arkansas Infantry Regiment was exchanged at camp near Washington, Arkansas, about October 1863, after which it was mounted and served as cavalry. At some point before the end of the war, the regiment was dismounted and merged into the 3rd Arkansas Consolidated Regiment. This regiment was around Marshall, Texas, when the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department surrendered in May 1865. There are no known muster rolls for the 19th Arkansas from the post-Vicksburg period.

If Asbury Hooks had avoided capture at Champion Hill, he would probably have been among the rest of the garrison that finally surrendered and would never have made his long odyssey to the Atlantic coast.

We don’t know if Asbury Hooks ever located and returned to the 19th Arkansas Infantry after his release from Fort Delaware. Apparently the unit still existed because Private A.H. Reynolds, in his memoirs, describes returning from his imprisonment at Fort Delaware:

“When I returned to my command I found Colonel Dockery promoted to Brigadier General, promoted for bravery at Champion Hill, Farmington. Corinth, Hatchey Bridge, Iuka, all of which battles were inscribed on our battle flag. It found a watery grave in the hands of Captain Godbold who perished with it in the Big Black River on the morning of May 17, 1863, as our command was falling back into Vicksburg. No officer was truer or braver than Captain Godbold, and he sacrificed his life rather than see his colors in the hands of the enemy. Heaven bless that noble soldier!

The Natchez Democrat says of General Dockery's war record:

"A more gallant soldier never wore the gray. With his own means he equipped the 19th Arkansas Regiment. He became its Colonel, and served with distinction in Cabell's Brigade at Corinth. Miss. His men were devotedly attached to him and were fond of telling that he never said 'Go on,' but 'Come on,' in the thickest of the battle. He was in Bowen's Division at Vicksburg, and there he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General. He was one of the leaders at the battle of Baker's Creek and Big Black; but perhaps he served with most credit for unflinching bravery and military skill at Champion Hill. Here his men did notorious fighting and were cut to pieces. The General had two fine horses shot under him and barely escaped himself. He was known afterwards as 'the hero of Champion Hill'."

General Dockery signed the instrument of surrender for the remaining Confederate troops in Arkansas in May, 1865, after Robert E. Lee had surrendered his troops at Appomattox April 12th. His property swept away by the war, General Dockery afterwards took up the profession of civil engineering, and lived for some years in Houston, Texas. His death occurred in New York City on February 27, 1898. His body was taken to Natchez, MS, the residence of his two daughters, for burial.

Epilogue:

Asbury Hooks eventually found his way back to Columbia County, Arkansas, and married Rebecca Ann Myatt. Rebecca Ann was the daughter of Eldridge Myatt, who was born in Tennessee and moved to Arkansas in the late 1840s. Eldridge initially settled in Calhoun County and later filed a claim for a land grant in Columbia County, Arkansas in 1852.

Asbury and Rebecca were married on November 22, 1866, in Columbia County and became the parents of nine children. Eldridge Myatt and Asbury Hooks eventually moved their families to White County and settled in Marshall Township, where they were listed in the 1880 census. Asbury was a farmer and his home was located a couple of miles southwest of Romance at the southwest corner of the intersection of Highways 5 and 310. He filed for a veteran’s pension in 1920 and on the application form indicated that he was discharged from his military service on or about April 1, 1865, or a little over three years from the date of his 12-month enlistment.

Asbury died December 7, 1922 at age 78 from the complications of old age and is buried in the Romance cemetery. Rebecca filed for a widow’s pension in 1923 and she died in 1924. She is also buried in the Romance cemetery.

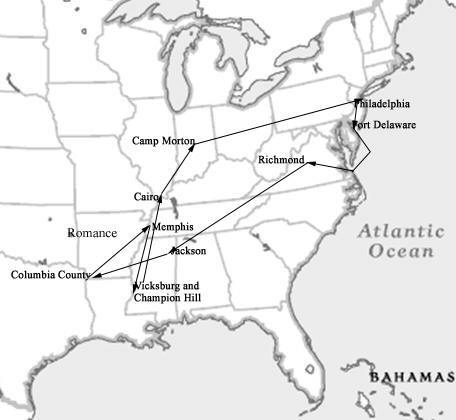

Asbury Hook’s Odyssey

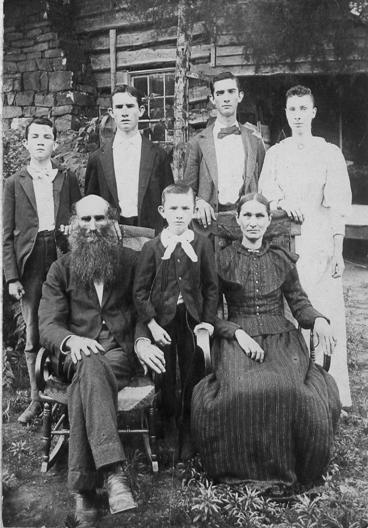

The Asbury Hooks Family

This photo of the Asbury Hooks family was probably taken in the early 1890s. The location appears to be in front of the log home where they lived near Romance. Seated in front are Asbury and his wife Rebecca with their youngest son Kenny Lester (b. 1886) standing between them.

Standing in the back are three more of the five sons who should have been living at the time. Besides Kenny, the other four boys were C. Vernon (b. 1881), James (b. 1878), Edmond (b. 1876), William (b. 1869, d. 1895). Also standing in the back is daughter Cora (b. 1874). Their oldest daughter, Martha (b. 1867) is not in the picture. Another son, Thomas, who was born in 1872 died in 1888. Another child, A.H., had been born in 1888 and died in infancy in 1889.